Does natural stone grow? How stones appear in nature. Spheroids in the world

Amazing stones can be found far from the cities in the center and south of Romania. Trovants – that’s what the locals call them. It turns out that these stones can not only grow, but also, much to our surprise, multiply.  Basically, these stones do not have sharp chips; they have a round or streamlined shape. There are a lot of different boulders in these areas, from which these unique trovant stones are not much different. However, after the rain, incredible events happen to the trovants: they grow like mushrooms, increasing in size. For example, a small trovant, which weighs only a few grams, can eventually grow to gigantic sizes and weigh more than a ton. The older the stone, the slower it grows. Young stones grow faster.

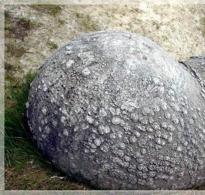

Basically, these stones do not have sharp chips; they have a round or streamlined shape. There are a lot of different boulders in these areas, from which these unique trovant stones are not much different. However, after the rain, incredible events happen to the trovants: they grow like mushrooms, increasing in size. For example, a small trovant, which weighs only a few grams, can eventually grow to gigantic sizes and weigh more than a ton. The older the stone, the slower it grows. Young stones grow faster.  The main component of growing trovant stones is sandstone. In terms of their internal structure, they also look unusual: if you cut a stone in half, then on a cut that looks like a tree cut, you can see several so-called age rings, concentrated around a small solid core.

The main component of growing trovant stones is sandstone. In terms of their internal structure, they also look unusual: if you cut a stone in half, then on a cut that looks like a tree cut, you can see several so-called age rings, concentrated around a small solid core.  But, nevertheless, geologists are in no hurry to classify trovants as phenomena inexplicable to science, despite their amazing origin. Scientists have come to the conclusion that although the growing stones are unusual, their nature can be easily explained. Geologists are confident that trovants are just the results of long-term sand cementation processes that take place over millions of years in the bowels of the earth. And with the help of strong seismic activity, such stones end up on the surface.

But, nevertheless, geologists are in no hurry to classify trovants as phenomena inexplicable to science, despite their amazing origin. Scientists have come to the conclusion that although the growing stones are unusual, their nature can be easily explained. Geologists are confident that trovants are just the results of long-term sand cementation processes that take place over millions of years in the bowels of the earth. And with the help of strong seismic activity, such stones end up on the surface.  Scientists have also found an explanation for the growth of trovants: stones increase in size due to the high content of various mineral salts located under their shell. When the surface gets wet, these chemical compounds begin to expand and put pressure on the sand, causing the stone to “grow.”

Scientists have also found an explanation for the growth of trovants: stones increase in size due to the high content of various mineral salts located under their shell. When the surface gets wet, these chemical compounds begin to expand and put pressure on the sand, causing the stone to “grow.”

Reproduction by budding

Nevertheless, the Trovants have one feature that geologists are unable to explain. Living stones, in addition to growing, are also capable of reproducing. It happens like this: after the surface of the stone gets wet, a small bulge appears on it. Over time, it grows, and when the weight of the new stone becomes large enough, it breaks off from the mother one. The structure of new trovants is the same as that of other, older stones. There is also a core inside, which is the main mystery for scientists. If the growth of a stone can somehow be explained from a scientific point of view, then the process of dividing the stone core defies any logic. In general, the process of reproduction of trovants resembles budding, which is why some experts have seriously thought about the question of whether they are a hitherto unknown inorganic form of life. Local residents have known about the unusual properties of trovants for hundreds of years, but do not pay much attention to them. In the past, growing stones were used as building materials. Trovants can often be found in Romanian cemeteries - large stones are installed as tombstones due to their unusual appearance. Some Trovants have another fantastic ability. Like the famous crawling rocks from California's Death Valley Nature Reserve, they sometimes move from place to place.Open-air museum

Today the trovants are one of those attractions in Central Romania that tourists from all over the world come to see. In turn, resourceful Romanians make souvenirs and decorations from small trovants, and therefore every guest has the opportunity to bring a piece of the stone miracle with them from their travels. Many owners of souvenir stones claim that commemorative items made from trovants, when wet, begin to grow, and they sometimes move around the house without permission, which produces a rather eerie impression. The largest accumulation of growing stones was recorded in the Romanian county (region) of Valcea. On its territory there are trovants of all shapes, sizes and colors. Due to the great interest of tourists, in 2006, the only open-air museum of trovantes in the village of Costesti was created by the Valcin authorities. Its area is 1.1 hectares. The most unusual-looking growing stones from all over the area are collected on the territory of the museum. For a small fee, those interested can view the exhibition and purchase small samples as souvenirs.In the center and south of Romania, far from cities, there are amazing stones. Local residents even came up with a special name for them - trovants. These stones can not only grow and move, but also multiply.

In most cases, these stones have a round or streamlined shape and do not have sharp chips. In appearance, they are not much different from any other boulders, of which there are many in these places. But after the rain, something incredible begins to happen to the trovants: they, like mushrooms, begin to grow and increase in size.

Each trovant, weighing just a few grams, can grow over time and weigh more than a ton. Young stones grow faster, but with age, the growth of trovante slows down.

The growing stones consist mostly of sandstone. Their internal structure is also very unusual: if you cut a stone in half, then on the cut, like a cut tree, you can see several age rings, concentrated around a small solid core.

Despite the uniqueness of trovants, geologists are in no hurry to classify them as phenomena inexplicable to science. According to scientists, although the growing stones are unusual, their nature can be explained. Geologists say that trovants are the result of a long process of sand cementation that took place over millions of years in the bowels of the earth. Such stones appeared on the surface during strong seismic activity.

Scientists have also found an explanation for the growth of trovants: stones increase in size due to the high content of various mineral salts located under their shell. When the surface gets wet, these chemical compounds begin to expand and put pressure on the sand, causing the stone to “grow.”

Reproduction by budding.

Nevertheless, the Trovants have one feature that geologists are unable to explain. Living stones, in addition to growing, are also capable of reproducing. It happens like this: after the surface of the stone gets wet, a small bulge appears on it. Over time, it grows, and when the weight of the new stone becomes large enough, it breaks off from the mother one.

The structure of new trovants is the same as that of other, older stones. There is also a core inside, which is the main mystery for scientists. If the growth of a stone can somehow be explained from a scientific point of view, then the process of dividing the stone core defies any logic. In general, the process of reproduction of trovants resembles budding, which is why some experts have seriously thought about the question of whether they are a hitherto unknown inorganic form of life.

Local residents have known about the unusual properties of trovants for hundreds of years, but do not pay much attention to them. In the past, growing stones were used as building materials. Trovants can often be found in Romanian cemeteries - large stones are installed as tombstones due to their unusual appearance.

Ability to move.

Some Trovants have another fantastic ability. Like the famous crawling rocks from California's Death Valley Nature Reserve, they sometimes move from place to place.

Cobblestones can move, although very slowly. To measure the average step, the researchers photographed one of the stones at large intervals. In the end it turned out that

Fourteen days later the stone moved 2.5 mm. It would seem minuscule! But this fact explains the huge number of walking stones known throughout the world.

Academic science was extremely skeptical about the experimenters’ statement, without, however, denying the “possibility of independent movement.” The strange movement is explained by the cooling or, conversely, heating of the soil, which, with some periodicity, either “sucks in” or, on the contrary, “pushes” stones out of itself, due to which they can theoretically move. The pulsation of stones due to ion exchange with air is also possible, as well as the absorption of water and carbon dioxide by the stone.

Any number of stones, anywhere, that “adore” movement. On the territory of Kazakhstan, not far from Semipalatinsk, there is a vast stretch of forest-steppe, which has long been called the Wandering Field. The local round boulders, for some reason, only in the winter months start running in different directions, plowing wavy, ragged furrows.

In 1832, tradesman salt trader Ivan Troitsky had the opportunity to observe the development of the phenomenon. In a letter sent to his brother Kirill in Omsk, he writes: “Stones do not roll. They run and crawl on one side, scattering sheafs of sparks that are noticeable even in the sun. The stones plow tolerably without sowing. That’s why nothing grows on the bald patches where they frolic. Gray air envelops them. It’s easier to breathe on the field than around it. At the same time, the soul is oppressed, melancholy rolls over. I’d rather get in the saddle and get out of there!”

The impressions of the salt merchant Ivan Troitsky are indistinguishable from what Anthony Petrushev, deacon of the Pereslavl Semyonovskaya Church, experienced at the end of the 17th century, unsuccessfully trying to calm down the Blue Stone, which haunted the Orthodox people because, buried deep, and even crushed by an earthen mound, it then serenely slept for six months, then suddenly shot out of the mound like a cannonball.

In winter, when they were being transported on a sleigh across Lake Pleshcheyevo, a stone fell off the sleigh, became red-hot, melted the ice, and sank to the bottom. Fishermen in clear weather saw a stone underwater. Slowly but surely he moved towards the shore. After 50 years, he returned to his original place - a windswept hillock. The stone no longer played pranks - after all, it was not disturbed.

Its Far Eastern brother, the one-and-a-half ton one, has shown and continues to show aggressiveness, entrenched at the western end of Lake Bolon since the creation of the world. “What does this magician do?” admires Russian geologist Ya.A. Skrypnik. - Either he lies motionless, then he begins to jump, then he slowly drags along the path, then he makes his way through the reeds. Resembling an ancient mossy turtle, it invites you to think - isn’t it reasonable?”

Chinese geophysicists, taking as a working hypothesis that the atypical behavior of boulders and cobblestones is obviously associated with emissions of strong gravitational and anti-gravitational energies from geopathogenic faults, they, armed with all-hearing and all-seeing equipment, went to Tibet, where they set up camp near the ancient Northern Monastery, monks whose biography of the so-called Buddha Stone has been compiled for a millennium and a half. According to legend, his palms were imprinted on the stone. This shrine weighs 1100 kilograms. It climbs a mountain 2565 meters high and descends from it along a spiral trajectory, drawing circles at the top and bottom points. Each ascent and descent exactly fits into 16 years. Circling around the mountain and at the top takes half a century.

Chinese scientists using laser rangefinders, acoustic, seismic sensors, and night vision devices have established that it is impossible to visually notice the movement of the boulder. However, the maximum speed it reaches reaches a third of a kilometer per hour. The creeping stone is enveloped in a faint glow. Low-pitched sounds are also heard, something like the inarticulate muttering of an old man.

The unusual nature of the Trovantes sometimes leads to the emergence of very bold and, at first glance, implausible opinions and hypotheses, the authenticity of which official science is in no hurry to recognize. A number of researchers, as already mentioned, believe that trovants are representatives of an inorganic form of life. The principle of their existence and structure have nothing in common with the same characteristics of already studied species of flora and fauna. At the same time, growing stones may turn out to be both the indigenous inhabitants of our planet, who have quietly existed side by side with humans for millennia, and representatives of unearthly life forms that fell to earth with meteorites or brought by aliens.

It is quite possible that people are looking for other forms of life in the wrong places; real aliens have been among us for a long time, and we simply do not notice them.

Science confirms whether stones grow in nature and got the best answer

Answer from Єывф Фывф[guru]

link

link

Answer from Dasha Lifanenko[active]

Amazing stones can be found far from the cities in the center and south of Romania. Trovants – that’s what the locals call them. It turns out that these stones can not only grow, but also, much to our surprise, multiply.

However, after the rain, incredible events happen to the trovants: they grow like mushrooms, increasing in size.

For example, a small trovant, which weighs only a few grams, can eventually grow to gigantic sizes and weigh more than a ton. The older the stone, the slower it grows. Young stones grow faster.

link

The main component of growing trovant stones is sandstone. In terms of their internal structure, they also look unusual: if you cut a stone in half, then on a cut that looks like a tree cut, you can see several so-called age rings, concentrated around a small solid core.

Geologists are confident that trovants are just the results of long-term sand cementation processes that take place over millions of years in the bowels of the earth. And with the help of strong seismic activity, such stones end up on the surface.

Scientists have also found an explanation for the growth of trovants: stones increase in size due to the high content of various mineral salts located under their shell. When the surface gets wet, these chemical compounds begin to expand and put pressure on the sand, causing the stone to “grow.”

Living stones, in addition to growing, are also capable of reproducing. It happens like this: after the surface of the stone gets wet, a small bulge appears on it. Over time, it grows, and when the weight of the new stone becomes large enough, it breaks off from the mother one.

The structure of new trovants is the same as that of other, older stones. There is also a core inside, which is the main mystery for scientists. If the growth of a stone can somehow be explained from a scientific point of view, then the process of dividing the stone core defies any logic. In general, the process of reproduction of trovants resembles budding, which is why some experts have seriously thought about the question of whether they are a hitherto unknown inorganic form of life.

Some Trovants have another fantastic ability. Like the famous crawling stones from California's Death Valley Nature Reserve, they sometimes move from place to place

We have something similar in Russia. For several years now, in the Kolpnyansky district of the Oryol region in the village of Andreevka and its environs, round blocks of stone have been appearing from underground, as if by magic, on the surface.

LISTEN, THE SO-CALLED "firf firf" wins

We have already talked a lot about the fact that stones have their own life history, although it is very different from the history of living beings. The life and history of a stone is very long: it is sometimes measured not in thousands, but in millions and even hundreds of millions of years, and therefore it is very difficult for us to notice the changes that accumulate in the stone over thousands of years. A cobblestone pavement and a stone among arable fields seem constant to us only because we cannot notice how gradually, under the influence of the sun and rain, the hooves of horses and the smallest organisms invisible to the eye, both a cobblestone pavement and a boulder on arable land turn into something new.

If we could change the speed of time and if we could, like in cinema, rapidly show the history of the Earth over millions of years, then in a few hours we would see how mountains crawl out of the depths of the oceans and how they again turn into lowlands; how a mineral formed from molten masses very quickly crumbles and turns into clay; how in a second billions of animals accumulate enormous layers of limestone, and a person in a split second destroys entire mountains of ores, turning them into sheet iron and rails, into copper wire and cars. In this mad rush, everything would change and transform with lightning speed. Before our eyes, the stone would grow, be destroyed and replaced by another, and, as in the life of living matter, all this would be governed by its own special laws, which mineralogy is designed to study.

A section through the Earth's crust showing individual zones of the Earth.

We will begin the study of the mineral life of the Earth from depths inaccessible to exploration - from the “magma” zone, where the temperature is slightly above 1500 ° C and where the pressure reaches tens of thousands of atmospheres.

Magma is a complex mutual solution-melt of a huge amount of substances. While it boils in inaccessible depths, saturated with water vapor and volatile gases, its own internal work is going on, and individual chemical elements combine into ready-made (but still liquid) minerals. But then the temperature drops - either under the influence of general cooling, or because the magma moves to colder and higher zones - and the magma begins to solidify and release individual substances. Some compounds turn into a solid state earlier than others; they crystallize and float or fall to the bottom of the still liquid mass. Little by little, the forces of crystallization attract more and more new ones to the solid particles that have arisen; the solid material comes together as it separates from the liquid magma.

Magma turns into a mixture of crystals - into that mineral mass that we call crystalline rock. Light granites and syenites, dark, heavy basalts are solidified waves and splashes of the once molten ocean. The science of petrography gives them hundreds of different names, trying to find in their structure and chemical composition the imprint of their past in the unknown depths of the Earth.

A section through a massif of granite, with branches of granite veins and the release of various metals and gases.

The composition of solid rock is far from the same as the composition of the molten source itself. A huge amount of volatile compounds permeates its molten mixture, is released in powerful jets, and permeates its cover; and its hearth smokes and smokes for a long time until the mixture completely hardens and turns into solid rock. Only an insignificant part of these gases remains inside the solidified mass, the other part rises to the earth's surface in the form of gas jets.

Not all of these volatile compounds have time to reach the earth's surface. A huge part of them is still deposited in the depths, water vapor condenses; Hot springs flow through cracks and veins to the surface of the Earth, slowly cooling and gradually releasing mineral after mineral from the solutions. Some of the gases saturate the waters and burst out to the surface of the Earth in the form of springs or geysers, while others soon find other paths and form solid compounds.

A void in rock formed when some rocks cool.

Hot springs - juvenile, young waters, in the words of the famous Viennese geologist Suess - are not the paths that connect the life of magmas with the life of the earth's surface. The number of hot springs is very large. In the United States of America alone there are at least ten thousand known, and in Czechoslovakia over a thousand, among which there are many healing ones, for example the famous hot spring in Karlovy Vary. From them, real water sources are formed, which bring with them substances alien to the surface from the depths, and minerals and sulfur compounds of heavy metals begin to precipitate along the walls of cracks, along the smallest cracks of rocks. This is how ore deposits arise from volatile compounds of deep magmas, and those accumulations of minerals that man so greedily seeks are born. On the surface of the Earth, all this mass of water, volatile compounds, gas vapors, solutions that were not retained along the way from the depths and did not settle in the form of various minerals - all this mass flows into the atmosphere and into the ocean, gradually, over many geological periods , bringing them to the modern state.

Thus, little by little, our air and our oceans were created with their current composition and properties - as a result of the entire long history of the Earth.

We're on the surface.

Above us is an ocean of atmosphere - a complex mixture of vapors, gases, earth and cosmic dust. Further than three kilometers from the earth's surface, the influence of the Earth's transformations is almost completely unaffected. There, beyond the noctilucent clouds, zones richer in hydrogen begin, and at the very border accessible to our research, lines of helium gas sparkle in the spectra of the northern lights. In the lower layers of the atmosphere, particles ejected by volcanoes rush around, dust swirls, raised by winds and desert storms - here a special world of chemical life opens up for us.

Before us are ponds and lakes, swamps and tundras with their gradual accumulation of rotting organic matter. In the mud and silt covering their bottom, their own processes take place: iron is slowly drawn into legume ores, complex decomposition of sulfur organic compounds occurs, forming concretions of iron pyrites, and there is not enough oxygen. Microscopic life continuously glows, causing and collecting more and more new products. In sea basins, in the expanse of ocean waters, these processes are even greater...

But let's move on to solid ground. Here is the kingdom of the mighty agents of the earth's surface - carbonic acid, oxygen and water. Gradually and steadily, grains of quartz sand accumulate here, carbonic acid takes possession of metals (calcium and magnesium), silicon compounds of the depths are destroyed and turned into clay. Wind and sun, water and frost help this destruction, annually carrying up to fifty tons of matter from every square kilometer of the earth.

Beneath the cover of the soil, a world of destruction stretches deep, and up to five hundred meters deep, processes of change take place, weakening in their strength and being replaced below by a new world of stone formation.

This is how we picture the inorganic life of the earth’s surface. There is intense chemical activity going on all around us. Everywhere old bodies are processed into new ones, sediments are deposited on sediments, minerals accumulate; the destroyed and weathered mineral is replaced by another, and new and new layers are imperceptibly laid on the free surface. The bottom of the ocean, the muddy masses of swamps or rocky river beds, the sandy seas of the desert - everything must disappear either in streams of flowing water, or in gusts of wind, or become part of the depths, covered with a new layer of stone. Thus, gradually, the products of the destruction of the Earth, escaping from the power of those on the surface and being covered with new sediments, pass into the conditions of the depths that are alien to them. And in the depths, rocks are resurrected in a completely new form. There they come into contact with a molten ocean of magma, which penetrates them, either dissolving or crystallizing minerals again.

Thus, the surface sediments again come into contact with the magma of the depths, and a particle of each substance makes its long journey many times in perpetual motion.

Stones live and change, outlive and turn into new stones again.

Stones and animals

We now know that there is a very close connection between stones and animals. The activity of organisms on earth takes place in a very thin film, which we call the biosphere. It is unlikely that its influence is felt particularly high in the atmosphere, although some scientists have discovered living germs of microbes in the air at an altitude of two kilometers. Air currents carry spores and fungi to a height of ten kilometers. And even condors rise to a height of seven thousand meters! Life penetrates no deeper than two thousand meters into the depths of the solid shell of the earth. Only in the seas and oceans, from the very surface of the waters to the greatest depths, do we find organic life. But even in the very surface film of the earth, the distribution of life is much wider than is commonly thought. Data from the famous Russian biologist Mechnikov suggest that some organisms withstand changes and fluctuations in conditions much greater than those experienced by the surface of the earth.

I remember the descriptions of one expedition, which observed powerful reproducing colonies of one bacterium on the snow and ice of the Polar Urals. These colonies grew so large that they gave rise to a soil cover on a continuous mass of polar ice. Along the shores of the boiling pools of the famous Yellowstone Park in the USA, certain types of algae grow, which, at temperatures close to 70°C, not only live, but also precipitate siliceous tuff.

The limits of life are much wider than we think: for example, for bacteria and molds or their spores, life remains within the range from +180 to –253°!

But in the very zone of the biosphere, in that film that we call soil, there this role of organic life is especially pronounced. In one gram of soil cover, the number of living bacteria ranges between two and five billion! A huge number of earthworms, moles or termites invariably loosens the soil, facilitating the penetration of air gases. Indeed, in the soils of Central Asia, the number of large living creatures (beetles, ants, flies, spiders, etc.) per hectare exceeds twenty-four million! The importance of microlife in the soil cover is absolutely invaluable. The famous French chemist Berthelot, speaking about the earth's surface, called the soil something living.

More complex creatures, through their life and death, participate in the chemical processes of mineral formation. We are well aware of how entire islands arise due to the life of polyps. Geology reveals to us an era when rows of coral reefs stretched for thousands of kilometers, accumulating calcium carbonate from sea waters in the complex chemical life of coastal areas.

Anyone who looked closely at our Russian limestones - perhaps the most widespread rock of the USSR - could easily notice what various remains of organic life they are made of: shells, rhizomes, polyps, bryozoans, sea lilies, urchins, snails - all this is mixed together in the total mass.

Where currents occur in the oceans, conditions are often suddenly created in which life for fish and other organisms becomes impossible. These underwater graveyards give rise to accumulations of phosphoric acid, and deposits of the mineral phosphorite in various rock deposits tell us that this process is not only happening now, but was going on before, in the distant geological past.

Some organisms participate in the formation of minerals through their lives, producing new stable compounds from the chemical elements of the earth, whether in the form of calcareous shells of phosphate animal skeletons or flint shells. Other organisms participate in the formation of minerals only after their death, when the processes of decay and decay of organic matter begin. In both cases, organisms are the largest geological details, and inevitably the entire character of the minerals of the earth’s surface will depend, as it already does, on history development of the organic world.

In this same zone of the biosphere, man acts as a powerful transformer, conquering the forces of nature. By transforming nature, man transforms its substances into those that have never existed in the biosphere before. It burns more than a thousand million tons of coal annually, wasting energy accumulated over long geological epochs for its own purposes. About two billion people live on the earth's surface, erecting grandiose buildings, connecting entire oceans, turning thousands of square kilometers of bare steppes and deserts into flowering fields.

Processing of rocks and minerals, increased industrial and factory activity, more and more new demands in the cultural life of mankind - all this is already a powerful factor in the transformation of stone.

In his economic activities, man not only uses the riches of the earth, but also transforms its nature: every year people smelt up to one hundred million tons of cast iron, millions of tons of other native metals, and in this way obtain minerals that only occasionally, as museum rarities, are produced by nature itself.

Stones from the sky

One hundred and seventy years ago the population of France was alarmed by a remarkable celestial phenomenon. In the same year (1768), stones fell from the sky in three places, and the amazed inhabitants believed in a miracle, contrary to everything that science said. In the evening, at about 5 o'clock, there was a terrible explosion. An ominous cloud suddenly appeared in the clear sky, and something fell with a whistle into the clearing, half crashing into the soft ground. The peasants came running and wanted to lift the stone, but it was so hot that they could not touch it. They fled in fear, but after a while they came again - the fallen stone was cold, black, very heavy and lay calmly in the old place...

The Paris Academy of Sciences became interested in this “miracle” and sent a special commission to check it; it included the famous chemist Lavoisier. But the possibility of a stone falling to Earth from heaven seemed so incredible that the commission, and after it the academy, rejected its celestial origin.

Meanwhile, the “miracles” continued: stones fell, their fall was confirmed by eyewitnesses. The Czech scientist E. F. Chladny was one of the first to rebel against the inert ideas of the Paris Academy and in his bold articles began to prove that stones really fall from the sky. Of course, such falls were often surrounded by fantastic stories, and ignorant people considered this stone a sacred talisman: sometimes it was crushed and taken as medicine. The stone that fell in 1918 near the city of Kashin was beaten by peasants, and its crushed fragments served as a “healing” powder for the seriously ill.

Now we know that Khladny was absolutely right when he said that every year stones fall, sometimes singly, sometimes in whole rains, sometimes in the smallest dust, sometimes in the form of heavy large blocks. Occasionally, they even kill people and cause fires, break through the roofs of houses, crash into arable lands or drown in swamps. We call such stones meteorites.

On the white snow of the polar regions, where the dust of cities, roads, and deserts does not fly, you can often notice the smallest dust “falling from the sky,” the composition of which reminds us so little of the ordinary minerals of our Earth. Some scientists think that several tens or even hundreds of thousands of tons, or many hundreds of carriages, of this “cosmic dust” fall to Earth annually. Among the meteorites there are colossi. In a huge crater, one and a half kilometers in diameter, they were looking for a large meteorite for a long time in America, in the state of Arizona. Now we have come across small fragments of that probably huge iron mass, which should contain half a billion rubles worth of pure iron, weighing almost ten million tons of metal; but the search for these riches is still in vain. Somewhere in the sands of the Sahara Desert lies another celestial giant; There are still unclear stories about it from Bedouins and Arabs who brought pieces of stone. Recently, a number of interesting studies have been sparked by the question of a huge meteorite, which on June 30, 1908 caused vibrations in the air and soil throughout Eastern Siberia and fell somewhere far away in the swampy taiga of Podkamennaya Tunguska. Precision instruments even in remote Australia noted this impact on our planet.

An expedition of the Academy of Sciences in 1927, led by the brave mineralogist L.A. Kulik, reached this place and found a completely fallen and burnt forest. Local Evenki residents said that the fall of the meteorite presented a terrible picture. The roar deafened the people, a terrible windfall felled trees, deer died, the earth shook - and all this happened on a clear, sunny morning. We don’t yet know where this giant lies, but we firmly believe that man will be able to unravel this mystery of the Siberian taiga.

The internal structure and composition of meteorites are very interesting. Some closely resemble our ordinary rocks, although they consist of some minerals that we do not know on Earth. Others consist of almost pure metallic iron, sometimes with droplets of a transparent yellow mineral - olivine.

We don’t know either such iron or such rocks on Earth, and therefore there is no doubt that they came to us from some other cosmic bodies. But from where? Maybe these are bombs from the Moon’s volcanoes, thrown out by it even when its molten surface was boiling? Or are they fragments of those small planets that revolve around our Sun between Jupiter and Mars? Or are these fragments of comets that accidentally flew in? I will not hide that we do not yet know the origin of our guests, and only bold guesses can so far tell us their history in the depths of the universe.

The time will come, and the accumulated information will reveal to us this secret of nature. To do this, you just need to be a good natural scientist, study in detail all the phenomena around us, accurately describe them, compare them with each other and find common features in some and differences in others. More than a hundred years ago, the famous French naturalist Buffon said quite correctly: “Collect facts, and from them an idea will be born.”

Likewise, the mineralogist of our time carefully collects meteorites, studies their composition and structure, compares them with earthly stones and makes a number of interesting conclusions and guesses.

Here is a rain of stones on January 30, 1868 in the former Lomzhinsk province - thousands of stones of various sizes in a black melted crust fall onto the ground and onto a newly frozen river, but the stones do not break through even a thin layer of ice.

Other meteorites are also known that fall obliquely to the ground (in Algeria in 1867), but with such speed and force that they tear out a long and deep groove over a whole kilometer. When falling, meteorites usually become very hot, sometimes heating up to temperatures above 2000°, but they heat up only from the surface, and inside the stone is usually very cold - so much so that your fingers freeze when touching it. Meteorites often break up in flight with strong explosions from friction with the air. Sometimes they crumble into dust or turn into rain, which scatters stones over several kilometers.

All these fragments are carefully collected and stored in various museums. The best collections of meteorites are kept in four museums: in our Mineralogical Museum of the Academy of Sciences in Moscow, in Chikayu, in London - in the British National Museum and in Vienna - in the National Museum.

We know many wonderful stories about stones falling from the sky, but none of them revealed to us the secrets of their origin.

The Cainzas meteorite was delivered to Moscow.“On September 13, pieces of a large meteorite fell on the field and forest of the Kainzas collective farm, located on the border of the Muslyumovsky and Kalininsky districts of Tatarstan. One of them, weighing fifty-four kilograms, almost killed collective farmer Mavlida Badrieva, who was working in the field. The air wave was so strong that Badrieva, who was four to five meters from the place where the meteorite fell, was knocked down and shell-shocked.

A huge fragment weighing one hundred and one kilograms fell in the forest, breaking off the branches of one of the trees. Recently, this meteorite, named “Cainzas” after the place where it fell, was delivered to the meteorite commission of the USSR Academy of Sciences. This stone fragment is the largest among meteorites of this type in the collection of the USSR Academy of Sciences. It is recorded in the inventory book of meteorites as No. 1090.

Along with this fragment, four more fragments were delivered to Moscow, including a meteorite weighing seven grams. This is the smallest meteorite found by local residents in the area where the fragments fell. Local collective farmers took an active part in the search for fragments.

On May 12 of this year, a stone meteorite weighing three kilograms fell on the territory of the Kyrgyz SSR. This meteorite, named “Kaptal Aryk”, was also delivered to the Academy. A prize was sent to collective farmer Aryk-bai Dekambaev, who discovered the meteorite.”

* * *

On a dark November evening, let's go outside and admire the starry sky. Strings of shooting stars light up in all directions. Some cosmic bodies unknown to us are rushing past the Earth in cosmic space, only briefly flaring up at the border of its atmosphere. Hundreds, thousands of falling stars are around us, but not a single one of them falls to our Earth on the days of stellar showers. Falling stars and stars that fell on our Earth are not the same thing, no matter how similar their flight is. But in any case, the stones that fell from the sky are also pieces of that starry sky that we admire on a frosty winter night, pieces of other worlds of the universe unknown to us.

There are no miracles in the world, but people usually call miracles what they have not yet understood. So let's step up our efforts and understand!

Stone in different seasons

Does the stone change with different seasons? Does it live like an annual plant, or is it more like a perennial conifer? Maybe, like a bird, he changes his colorful outfit or, like a snake, sheds his skin every year? Of course, I would like to answer first of all: no, the stone is dead, lifeless and does not change either in spring or winter. I am afraid, however, that this answer will be a little hasty, since many minerals are formed and changed at certain periods of the year.

We know of one such very characteristic mineral that appears in certain months of the year, disappears in the spring over vast areas of the earth, only to return again in the fall. These are hard water, ice and snow. At first glance this seems a little strange, but remember that sometimes ice is known as an ordinary rock like limestone, sandstone or clay. In the Yakut region, ice occurs in whole rocks, interlayered with sand and other rocks.

If we lived in an environment of eternal cold, 20-30 degrees below zero, then ice would be for us the most common rock that would form rocks and mountains, and we would call its molten state water. We would perhaps consider water to be a very rare mineral and would rejoice when somewhere by chance, under the influence of the bright rays of the sun, liquid ice would appear, just as we are amazed by the molten sulfur of volcanoes or a drop of mercury frozen in a thermometer.

But we should not only call ice and snow temporary minerals - there are many such minerals, and we meet them at every step in spring and autumn, in polar countries and deserts.

In the spring near Moscow, after the spring waters have subsided, beautiful greenish-white flowers appear on the black clay: these are salts of iron sulfate, which is formed during the oxidation of pyrites by oxygen-rich spring waters. These substances cover the slopes of the beams in a motley pattern. But the first rain washes them away until next spring.

Even more striking is the picture of these bleachings in the desert. Here, in the wild conditions of the Kara-Kums, I had to encounter an absolutely fantastic appearance of salts. After a heavy night rain, the next morning the clayey surfaces of the shores are suddenly covered with a continuous snow cover of salts - they grow in the form of twigs, needles and films, rustling underfoot... But this continues only until noon - a hot desert wind rises, and its gusts dissipate within a few hours salt flowers. And again in the evening we see the same gray and gloomy desert desert.

Such seasonal minerals are even more impressive in our Central Asian salt lakes and especially in the famous Karabogaz Bay of the Caspian Sea. In winter, millions of tons of Glauber's salt fall there and, like snow, are thrown ashore by waves, only to dissolve again in the warm water of the bay in the summer.

However, the polar regions give us the most wonderful stone flowers. Here, during six cold months, in the salt brines of Yakutia, a former exile under the tsarist regime, mineralogist P. L. Dravert observed remarkable formations. In cold salt springs, the temperature of which dropped 25° below zero, large hexagonal crystals of the rare mineral “hydrohalite” appeared on the walls. By spring they crumbled into powdered simple table salt, and by winter they began to grow again. According to Dravert, “it seemed sacrilege to walk on this shiny, patterned crystalline surface, it was so beautiful.”

One cannot read Dravert’s letters about his discovery and first studies of hydrohalite without excitement. The crystals had to be removed from the brine, the temperature of which was 29° below zero. To determine the hardness of a crystal, it was necessary to draw ice or plaster with it at an air temperature of –21°. Even in the room where he tried to do chemical experiments, it was 11 degrees cold.

Damn town.

This is how he describes his research on this temporary mineral of polar Yakutia:

“Naturally, the idea arose in me to somehow record the shapes of the crystals. First I decided to make their prints in plaster and fill them with lead. But I didn’t have plaster; the beautiful transparent plaster that I found in Kyzyl-Tus still remained there and was not delivered to me. I went on a search and four miles from the dwelling I found outcrops of bad plaster, but here I was glad for it like sugar. Burned, crushed, sifted, etc. And, oh horror, the crystals broke and melted, entering the mass, and in the cold it froze, and then the crystal could not be clothed with it. Having wasted a lot of material, I ended up with several pitiful castings. By the way, all the spoils came out, and we had to use teaspoons... We had some butter left (we were often starving then; there was no bread anymore); With the permission of my companions, I used oil, intending to fill the prints in oil with plaster. We managed to make several forms; I exposed them to the cold to strengthen them; but two hours later, looking at the filling, I did not find a single piece - the yellow mice carried them away. I almost cried...

There was no other canning material, or I didn’t know a way. Suddenly a dagger-sharp idea flashed through my brain: ignis sanat!

In the dilapidated house where we lived, there was a Russian stove, which was heated continuously, because the chimney had no views. I placed several crystals in front of its mouth, at varying degrees of distance from the fire. The heat was so strong that this manipulation was carried out with leather gloves. The crystals began to melt, then, having lost part of the water, some remained in a slightly changed form (in shape), others began to produce branched processes like cauliflower, completely distorting their outlines...

For several days I stood in front of the stove, varying the experimental conditions. Finally I achieved that the crystals retained their appearance. To do this, they had to be dried in front of the mouth of a stove heated with dry wood, placed on a porous base that quickly absorbed their crystallization water.”

This is how the periodic minerals of Yakutia, these wonderful winter flowers of the salt springs of polar Siberia, were studied.

I have given just a few examples - those where changes in the stone are noticeable at different times of the year. But I think that if we were armed with a microscope and the most accurate chemical balances, we would see that many other minerals live the same unique life and constantly change in winter and summer.

Age of the stone

Is it possible to determine the age of a stone? “Of course not,” the reader will answer, knowing how difficult it is to determine the age of an animal or plant. After all, a stone exists for a very long time, the beginning and end of its life are lost somewhere in the unknown depths of time. But this is not entirely true, and sometimes the mineral itself records its age.

On one of my trips to Crimea, I had to study the sediments of the Saki salt lake. The surface of its black healing mud is covered with a durable gypsum crust. When they take mud for baths, they try to remove this crust. But it crumbles into small needles and sharp pebbles.

In these spear-shaped crystals I noticed black stripes, and comparing the gypsum needles with each other, I soon saw that the black stripes lie horizontally in the bark and always at the same level. The solution became obvious: gypsum crystals grow annually, especially in summer, after spring floods, when muddy silty waters flow into the lake from the surrounding mountains, causing the formation of black stripes on the gypsum crystals. Each stripe is a year of life, an annual ring - like those that we see so clearly on tree trunks. The crystals unexpectedly told the story of their formation, their age was no more than twenty years, and by the thickness of the clean and black stripes one can tell whether the spring was rainy and whether the summer was hot.

The same annual rings, but on a much larger scale, can be seen in the famous salt mines of Ukraine. Here, underground, in huge chambers illuminated by electric lamps, on the walls you can see stripes of different shades, regularly alternating throughout the underground halls. We know that these are annual rings of salt deposits in shallow lakes off the coast of the long-vanished Permian Seas.

But even more remarkable are the ribbon clays, which are found in large quantities in our North. They are sediments of lakes and rivers that flowed from that huge glacier that covered our North about twenty thousand years ago, penetrating in separate tongues far to the south, even into the region of the southern Russian steppes. In such clays, the color and size of the grains can be used to distinguish the winter layer, which is darker, and the summer layer, which is lighter. By counting such layers - and there are many thousands of them - it is possible to draw the exact chronology of our North. Ribbon clays are for a geologist a calendar in which the chronicle of our entire North was noted and recorded.

In mineralogy there are still much more accurate methods for determining the age of different stones. Most rocks and a large number of minerals contain radium, a rare metal, which itself is formed from other metals and, in turn, is gradually and slowly converted into other substances and especially into lead. In this case, helium gas is constantly released from radium. And the more radium changes, the more special lead and helium gas accumulate with it. If we only know how much radium is in the rock, how much lead is formed from it annually, then by the amount of lead we can determine the period of time that has passed since the beginning of the process, since the formation of the mineral.

Now it is more or less certain for us that the age of the most ancient minerals and rocks is determined between one thousand and two thousand million years. The rocks of Finland and the White Sea coast are probably one billion seven hundred million years old. Our coal deposits of the Donetsk basin were formed about three hundred million years ago. Now, for the first time, thanks to the stone, we have been able to construct a chronology of the world:

The formation of planets in our solar system up to 5–10,000,000,000 years ago.

Formation of the solid earth's crust - 2,100,000,000.

The appearance of the first life - 900,000,000–1,000,000,000.

Appearance of crustaceans (blue clay in the vicinity of Leningrad) - 500,000,000.

Appearance of armored fish (Devonian) - 300,000,000.

Coal era - 250,000,000.

The beginning of the Tertiary era and the time of formation of the Alpine Mountains - 60,000,000.

The appearance of man is about 1,000,000.

The beginning of the ice ages - before 1,000,000.

End of the last ice age - 20,000.

Beginning of fine stone processing - 7000.

Beginning of the Copper Age - 6000.

Beginning of the Iron Age - 3000.

Present moment (BC) - 0.

This is the definition of time in the past according to stone documents of natural history. Then the chronology breaks off. Outside the geological history of the Earth and the history of the Sun, the past is still hidden from the inquisitive thoughts of the scientist. Let, however, in the above figures the reader see only a first approximation to the truth: while milestones are only being outlined, they are trying to measure the time of the past. Human thought still experiences a lot of work, a lot of mistakes until it is able to construct an accurate chronology of the world from the approximate numbers of our chronology and reads its past from the chronicles of stone.

Scientists will still have to work a lot to use chronology in life itself and be able to make the age of plants and animals into accurate clocks of the past.

Notes:

Figures corrected according to D.I. Shcherbakov, Nature magazine, July 1952 ( Editor's note.)